Frank Yamaki lived in Northport for less than twenty years, but he left the community an invaluable legacy and an unsolvable mystery. After emigrating from Japan in the 1880s, Yamaki came to Northport to work as a cook. He prospered, became a popular member of the community, and in 1895 bought Benedict Warner’s photo studio on Woodbine Avenue.

His work as a photographer created his legacy to the community. He was very successful commercially, taking numerous portraits and wedding photos, but he also produced about 300 photographic plates that visually documented much of Northport Village at the turn of the Twentieth Century.

In 1979, Stephen Cavagnaro donated these prints to the Northport Historical Society. The Society then published a selection of the prints in a volume entitled Photographs of Old Northport. This slim volume provides a detailed glimpse into the life of the Village over a hundred years ago.

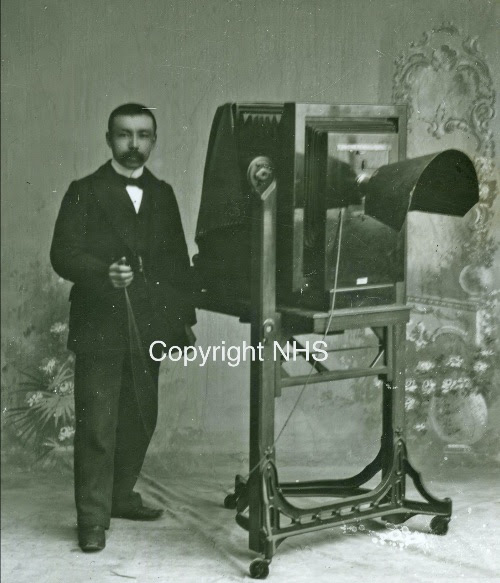

Trick Shot: Frank Yamaki, "self-portraits" in his studio on Woodbine Avenue

In contrast to the clarity of this legacy stands the dark mystery of Yamaki's marriage and death within five months, and the rumors that he was descended from Japanese royalty.

On October 1, 1905, Yamaki and Belle Pauline Brown, described by The Washington Times as "one of the handsomest of the younger summer cottage set in Northport" revealed to her parents that they had secretly been married on July 16, three days after they had met and twelve days before they had announced their engagement. The nuptials were covered in The Washington Times in an article that alluded to Yamaki's royal Japanese ancestry. Following a brief honeymoon, the couple moved to the Browns' Northport home.

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/2448996/the-brooklyn-daily-eagle/

Then, on November 6, Yamaki went missing. Later that week, the Long Islander reported that he “had closed his place of business…telling his wife he was going to King’s Park, and has not been seen since.” On November 20, his wife and her family moved back to their Brooklyn residence. On Thanksgiving Day, a hunter came across Yamaki’s body in the woods in East Northport. The coroner later ruled his death a suicide by poisoning.

The news of Yamaki's death spread and an article in The Washington Times from Friday, December 1, 1905 featured the headline: Princely Samurai Dies from Poison: Jap Who Wed White Girl Found Dead*

Excerpts below:

"It was thought at the time that the young woman had only been married to a prosperous photographer, but it was said afterward that her husband was a Japanese prince, and papers found on his body yesterday seemed to bear out the report. There were letters of introduction written on princely stationery and it was said also that Yamaki had been in receipt of a monthly allowance from Japan until recently. It was the sudden cutting off of this allowance which is given as the reason for his having killed himself.....The news of her husband's death came as a great shock to the young widow last night. She had a quarrel with her husband several days before he disappeared and she returned to the home of her parents in Brooklyn."

*This headline illustrates the prejudices of the era and when reviewing historical documents related to Yamaki's time in Northport, it is often noted that he was "very well liked" and was active in Northport's Methodist Church. He also tried repeatedly to become an American citizen but because citizenship at that time required one to be white or of African descent, he did not qualify.

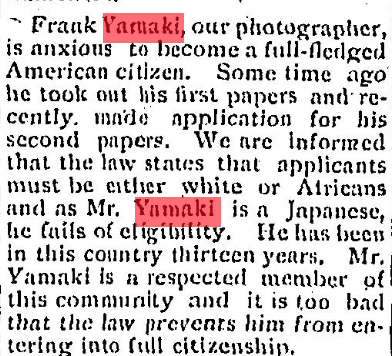

The Long Islander, June 8, 1900

The cause of Frank Yamaki’s mysterious death has never been determined. Bankruptcy has been suggested, but by most accounts the photography business was successful, and according to an interview with his mother-in-law that appeared inThe New York Times on the day of his funeral, he received a monthly check from Japan for $1500. Mrs. Brown further suggested that it was a threat of assassination for having disgraced the emperor by not returning to Japan at the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War that drove him to take his own life.

A note addressed to his wife found on Yamaki’s body further confounded the issue. It read:

My Dear Belle:

Forgive me for doing this. I can’t stand it no longer. This will end all. Good bye. Please forgive me Belle, I can not and will not tell.

With this final message, the man who provided a definitive look into the life of his times in Northport also bequeathed to later generations an intriguing, enduring mystery.

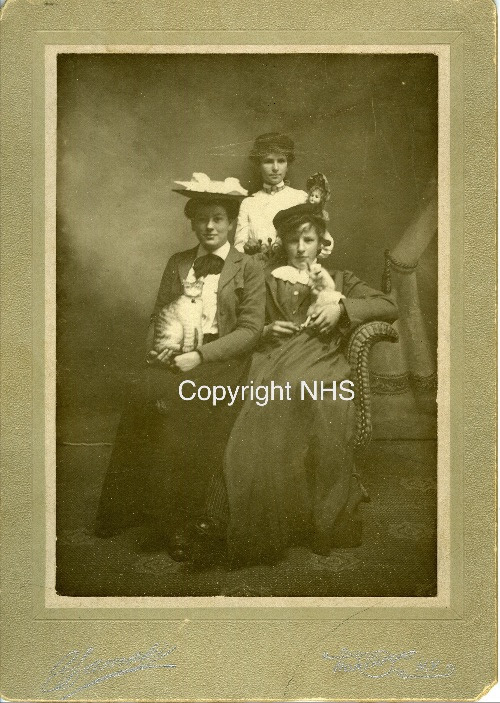

Portrait of Northport Ladies, photographed by Frank Yamaki

This article was taken from one of many booklets written and compiled by Bob Little - a teacher, Northport Historical Society member and Northport Library Trustee who has since passed away. The Society is proud to recognize Bob's wonderful contributions to the Northport Historical Society and our Northport community. His wife Darcy is still active in the Society and docents in the Museum on Wednesdays.